Global impact of U.S. trade restrictions on supply chains and production costs

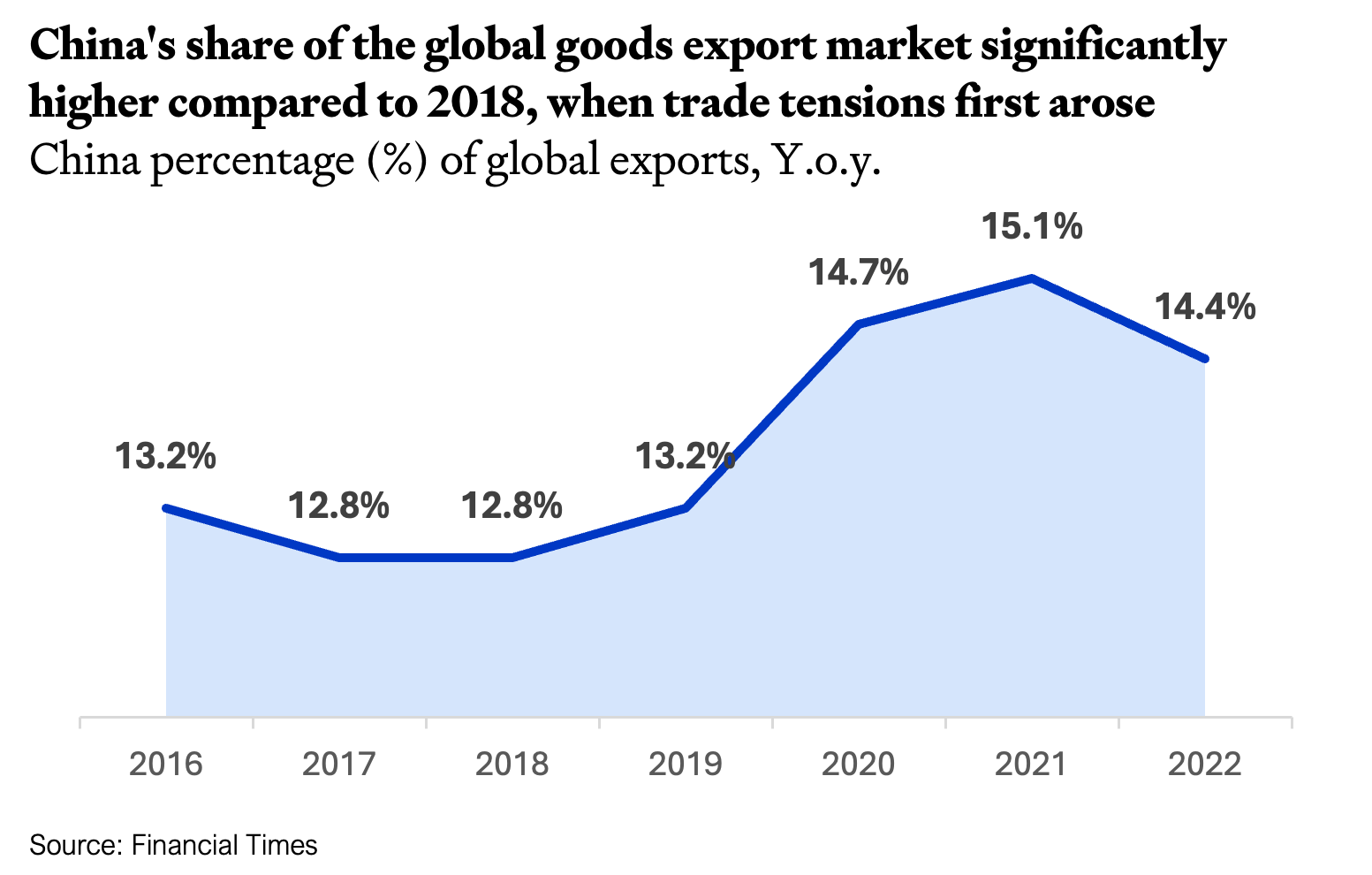

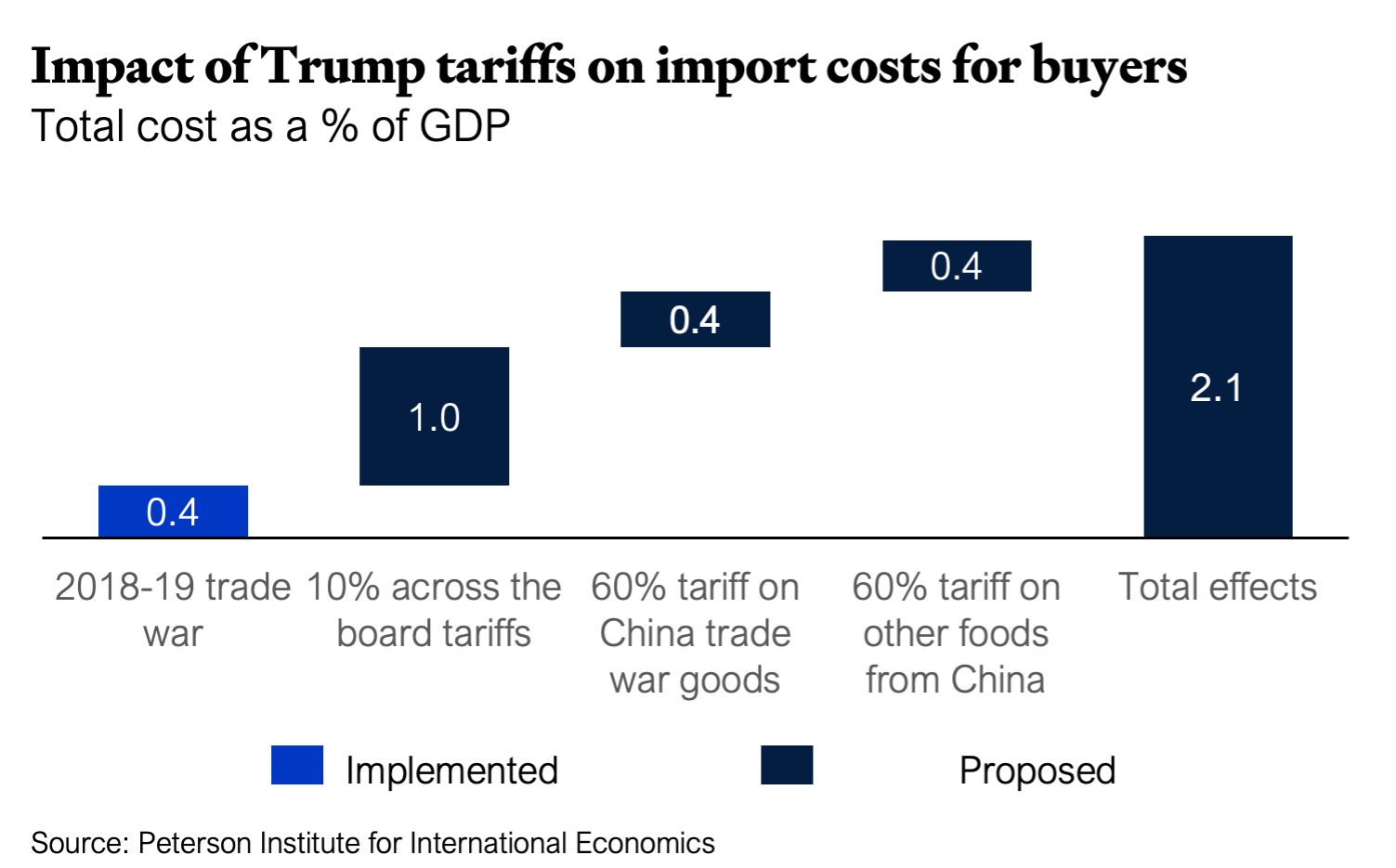

The impact of trade restrictions often extends beyond the immediate countries involved or the targeted products. For example, Western companies that outsource to or invest in China to export goods to the U.S. are directly impacted by U.S. trade restrictions on China. Consequently, U.S. tariffs on Chinese imports also impact non-Chinese firms. Additionally, higher tariffs on Chinese intermediate goods may raise production costs for U firms that rely on these imports; Tesla, which uses Chinese components in its U.S. manufacturing, faces increased costs under higher tariffs. The negative effects of the tariffs imposed by the Trump administration in 2018 for the U.S. economy amounted to significant shifts in its supply-chain network, a reduction in the variety of available imports, and increasing costs in the domestic prices of imported goods (Wolf, 2024).

Additionally, president-elect Trump has proposed a blanket tariff of 10 percent on all imports, with an aggressive 60 percent tariff specifically targeting Chinese goods.