New firms play a crucial role in the economy by introducing disruptive technologies, creating social mobility opportunities, and fostering labour market dynamism. Just as societies must nurture and support younger generations to thrive, economies also benefit significantly from the contributions of new businesses. Without them, economic growth and innovation would stagnate. A key distinction exists between self-employment and salaried positions, with employment choices often shaped by specific economic conditions. This distinction is particularly relevant in Italy, where self-employment serves as both a marker of economic vitality and a driver of job creation. Self-employed individuals challenge existing companies, fueling competition and innovation.

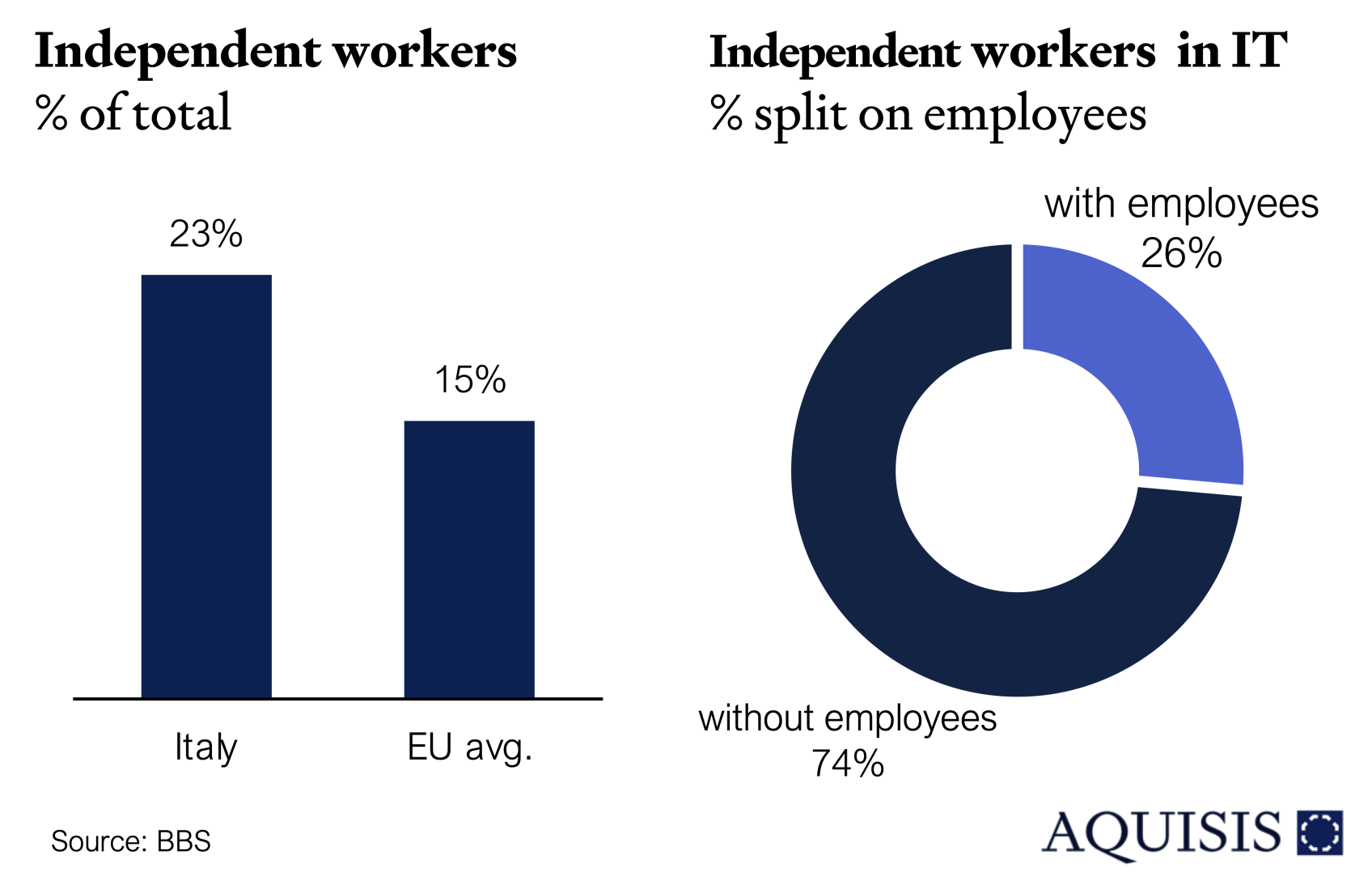

According to ISTAT 23% of Italy’s active labour force is independent workers, significantly higher than the 15% EU average, however they include 74% freelancers / solo-entrepreneurs. Notably, necessity-driven entrepreneurship was 50% more common in Italy than in the rest of Europe (15.8% vs. 10.5%) (Sobrero, 2020).

Entrepreneurs in the sense of running a fully fledged company represent just 1% of Italy’s total workforce, and their numbers remained stable between 2008 and 2018. However, Italy has one of the lowest rates of new business creation in Europe. According to a 2019 report, only 4% of adults aged 18-64 had started a business in the past three years. Alarmingly, 90% of them did so out of necessity, citing limited job opportunities rather than seizing market opportunities.

Where do new ventures come from? According to the latest AlmaLaurea report on student entrepreneurship, more than 2.2mn individuals graduated from Italian universities between 2008-2018. Of these, 150k (7%) started a company, with nearly ⅔ launching their ventures within two years of graduation. In total, around 170k companies were established. However, evidence from various countries suggests that most entrepreneurs gain experience before starting their own ventures (Sobrero, 2020).

Italy provides numerous examples of this phenomenon, where leading firms play a crucial role in training employees who later leave to establish their own companies at different stages of their careers. The history of IMA is a prime example of how small, family-owned businesses have evolved into the backbone of Italian manufacturing. IMA’s story began in 1961 when Andrea Romagnoli partnered with his brother-in-law Renato Taino. At the time, Romagnoli was the CTO at GD, following a stint at ACMA, two pioneers in industrial automation in Italy. A few years later, the Vacchi family joined the founders to develop a core business in food packaging machinery. Over the decades, IMA successfully navigated multiple technological shifts within the packaging industry, ultimately becoming a globally recognized leader.

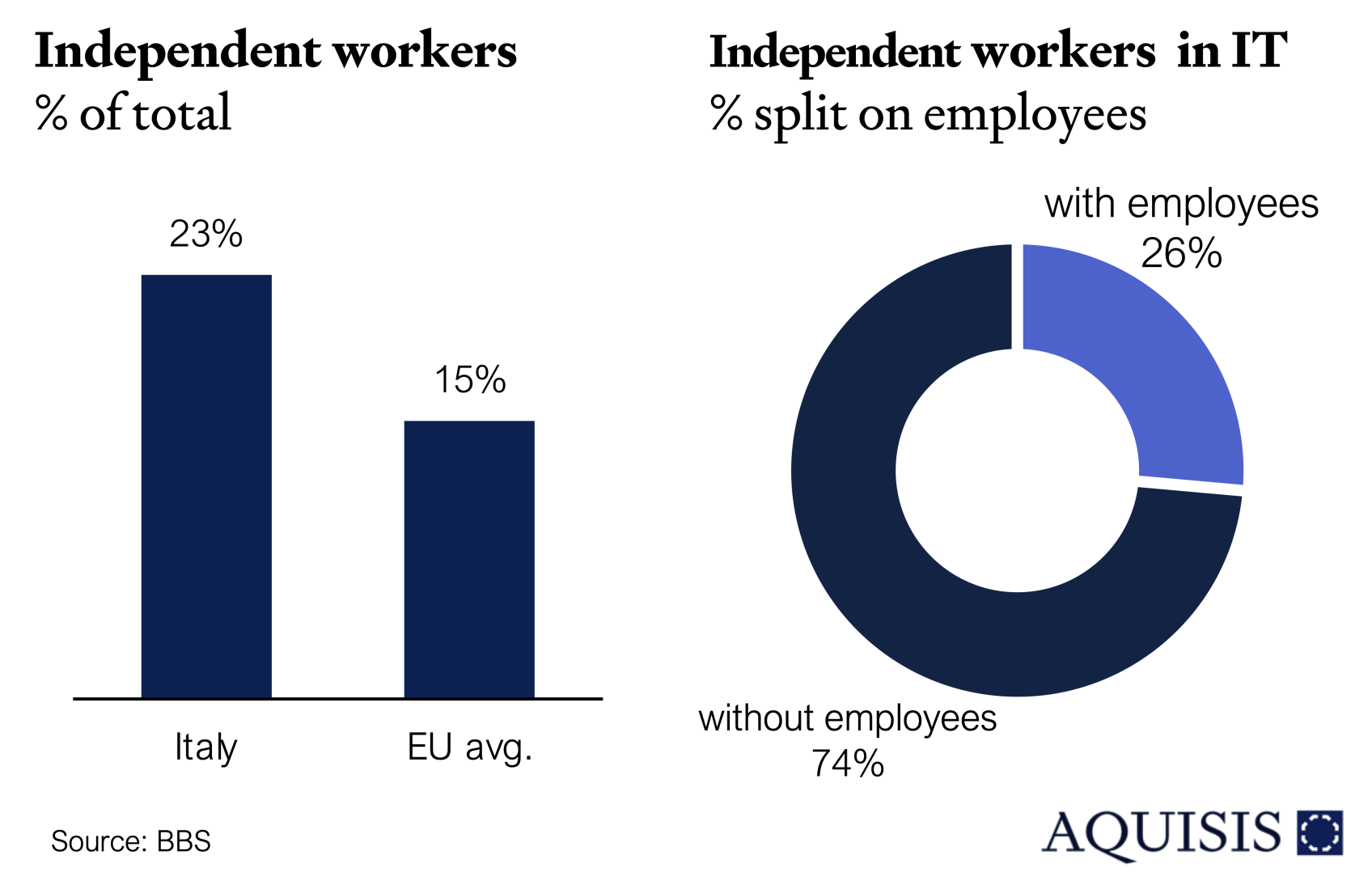

While entrepreneurship plays a key role in shaping economic growth, Italy’s broader economy has struggled to recover from the 2008 financial crisis. In 2023, “GDP volumes stood at a level higher than the maximum reached before the 2008 financial crisis for the first time,” stated ISTAT. Reaching pre-crisis output levels is undoubtedly a positive development. It’s good news for Italy. It’s good news for the debt sustainability of Italy. However, while ISTAT revised Italy’s public deficit-to-GDP ratio downward due to the economy’s larger size, this milestone also underscores the sluggish pace of Italy’s recovery compared to other advanced economies:

By contrast, Canada and the U.S. had already returned to their 2007 output levels by 2010. As of last year, the U.S. economy had grown by ⅓ since then. Germany and France reached this milestone in 2011, with their economies now about 15% larger than in 2007. The UK surpassed its pre-crisis GDP a decade ago and is currently 19% above that level. “The 2015–2019 recovery was not strong enough to bring output back to pre-global financial crisis levels, with 2008 GDP levels only being reached last year. This is in stark contrast to other advanced economies,” noted Nicola Nobile, an economist at Oxford Economics (Romei, 2024). Population decline does not help here, but is not the key culprit: Even on a per capita basis, there is a 22%-point gap to the US.

Italy faces several structural challenges that have contributed to prolonged economic stagnation. While some recent measures have provided temporary support, deeper issues persist. These will be explored in greater detail in a forthcoming article.

Italy’s economic structure is further shaped by its distinct regional dynamics, traditionally marked by a divide between the North and the South. However, national cohesion is maintained through common denominators such as a shared language (with minor exceptions), national institutions like state universities and a centralized government. Over the past two decades, regional influence has expanded due to devolution policies and the EU’s emphasis on regional development, raising questions about how innovation is distributed across the country.

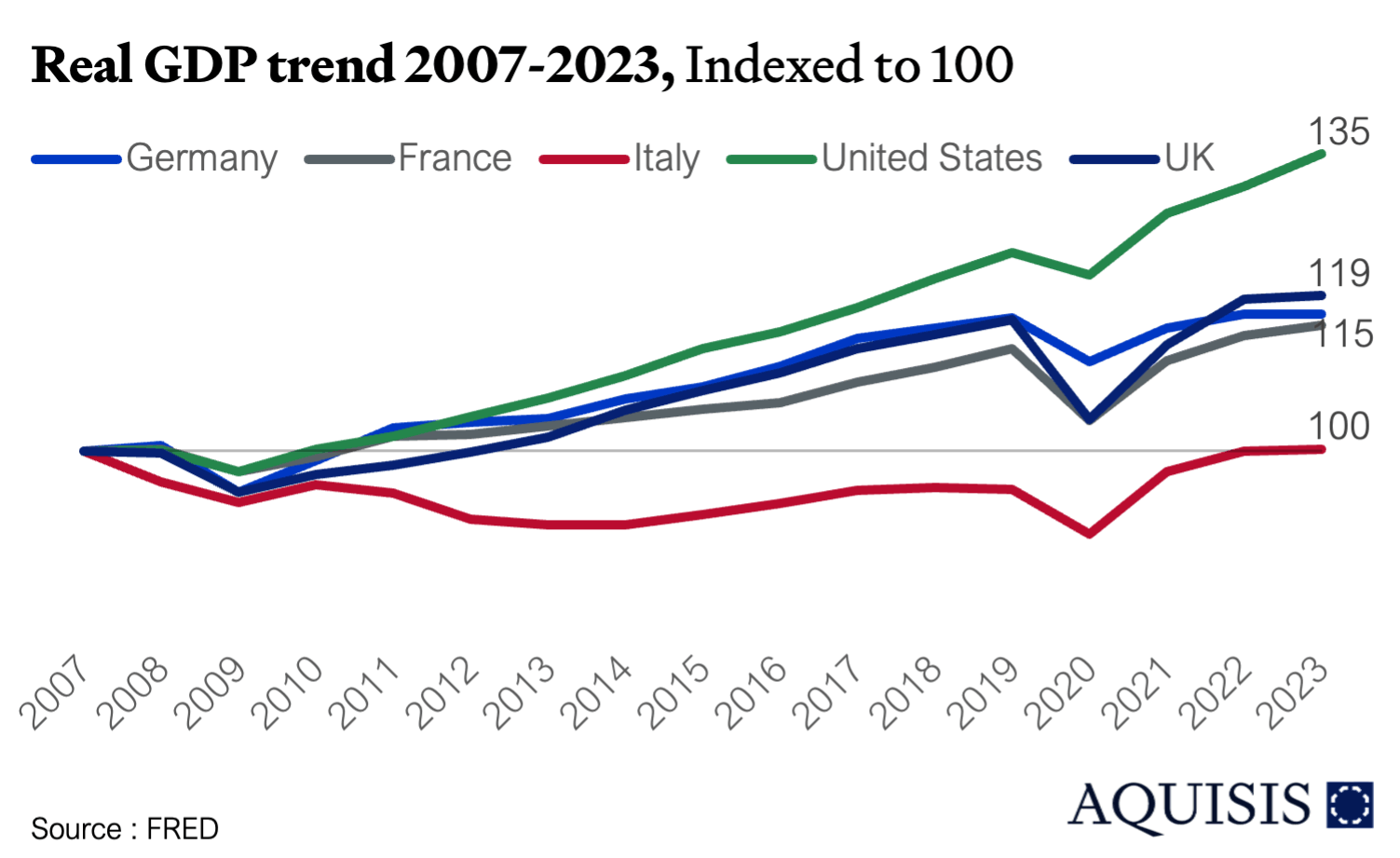

Italy’s innovation system is influenced by the balance between national and regional dynamics. Northern Italy, including Tuscany, has a well-developed network for innovation. Together, these regions make a strong contribution to national synergy, but their impact grows significantly when viewed as a single system. A similar trend is seen in Southern Italy, where the combined contribution of the twelve southern regions increases when treated as a unified system. National synergy is calculated as how effectively regions collaborate and contribute the country’s overall innovation network by assessing knowledge flows, business exchanges, and technological development (Loet Leydesdorff I. C., 2018).

Of course, Italy is not a black-and-white cut into two distinct parts. Leyesdorff proposes an alternative model that divides Italy into three regions: North, Central, and South. Under this approach, Tuscany shifts to Central Italy, increasing the region’s overall contribution. The difference in innovation synergy between the models is insignificant, which highlights the complexity of a multi-centric country like Italy: There are multiple centres of gravity for economic activity, sector excellence, and innovation, and they interact with each other. Still, there are meaningful regional disparities, and the Italian innovation ecosystem and economy would benefit from further integration.

Rome and Milan function as central hubs for innovation, followed by Florence and the Venice region. Unlike Spain, where Madrid and Barcelona operate as independent innovation systems with little integration into the rest of the country (Loet Leydesdorff I. P., 2019), Italy’s innovation ecosystem is more interconnected, particularly in medium-high-tech manufacturing and knowledge-intensive services.

This pattern of knowledge transfer, specifically from established firms to new ventures underscores the importance of open business networks. While new firms drive innovation by introducing fresh ideas, their success often hinges on connections to existing industries and experienced entrepreneurs. Interestingly, regardless of the type of knowledge being exchanged at local, regional, and national levels, family firms tend to connect primarily with other family firms. In contrast, non-family firms do not exhibit the same preference when exchanging knowledge with other non-family firms (Stefano Ghinoi, 2023). These findings suggest that ownership structure plays a significant role in shaping knowledge exchange patterns.

However, as IMA’s success illustrates, innovation thrives when businesses embrace external knowledge sources and break out of closed networks. Since knowledge transfer is a key driver of innovation, family-owned firms may benefit from expanding their networks beyond similar businesses. By fostering connections with a diverse range of firms, they can enhance their access to new ideas and innovative practices, ultimately strengthening their competitive advantage. This lesson is particularly relevant for Italy’s regional innovation landscape, where interconnected networks amplify economic and technological progress. Encouraging greater collaboration between family and non-family firms could enhance national synergy, ensuring that Italy’s innovation system remains competitive.

Associate

Managing Partner

Loet Leydesdorff, I. C. (2018). Regions, Innovation Systems, and the North-South Divide in Italy. The Evolutionary Dynamics of Discursive Knowledge .

Loet Leydesdorff, I. P. (2019). Measuring the expected synergy in Spanish regional and national systems of innovation. The Journal of Technology Transfer.

Romei, V. (2024, September 23). Better late than never: Italy’s back! Financial Times.

Sobrero, R. F. (2020). Entrepreneurs: born or raised? BBS Initiative for sustainable society and business.

Stefano Ghinoi, R. D. (2023). Family firm network strategies in regional clusters: evidence from Italy.

AI Website Software