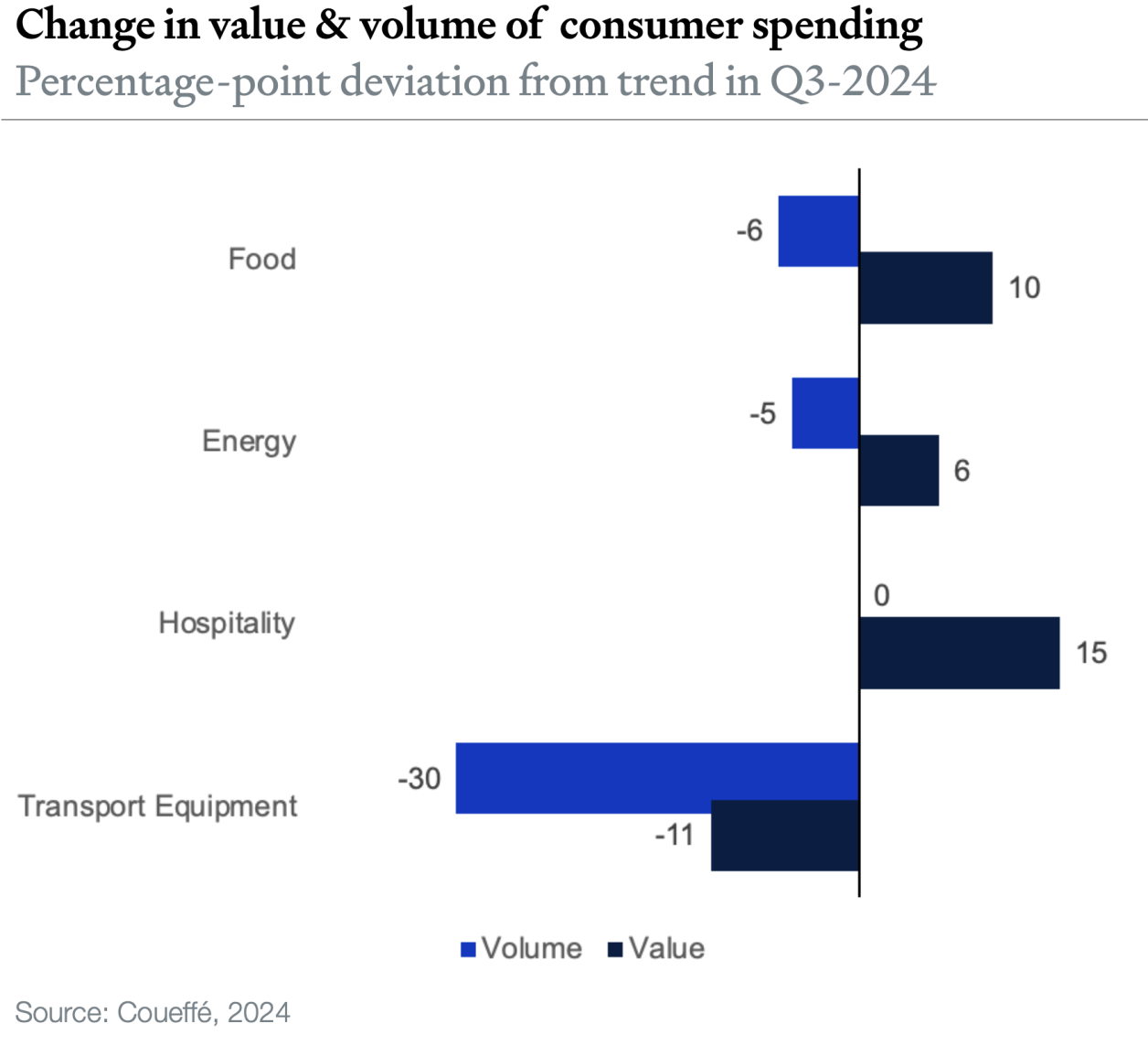

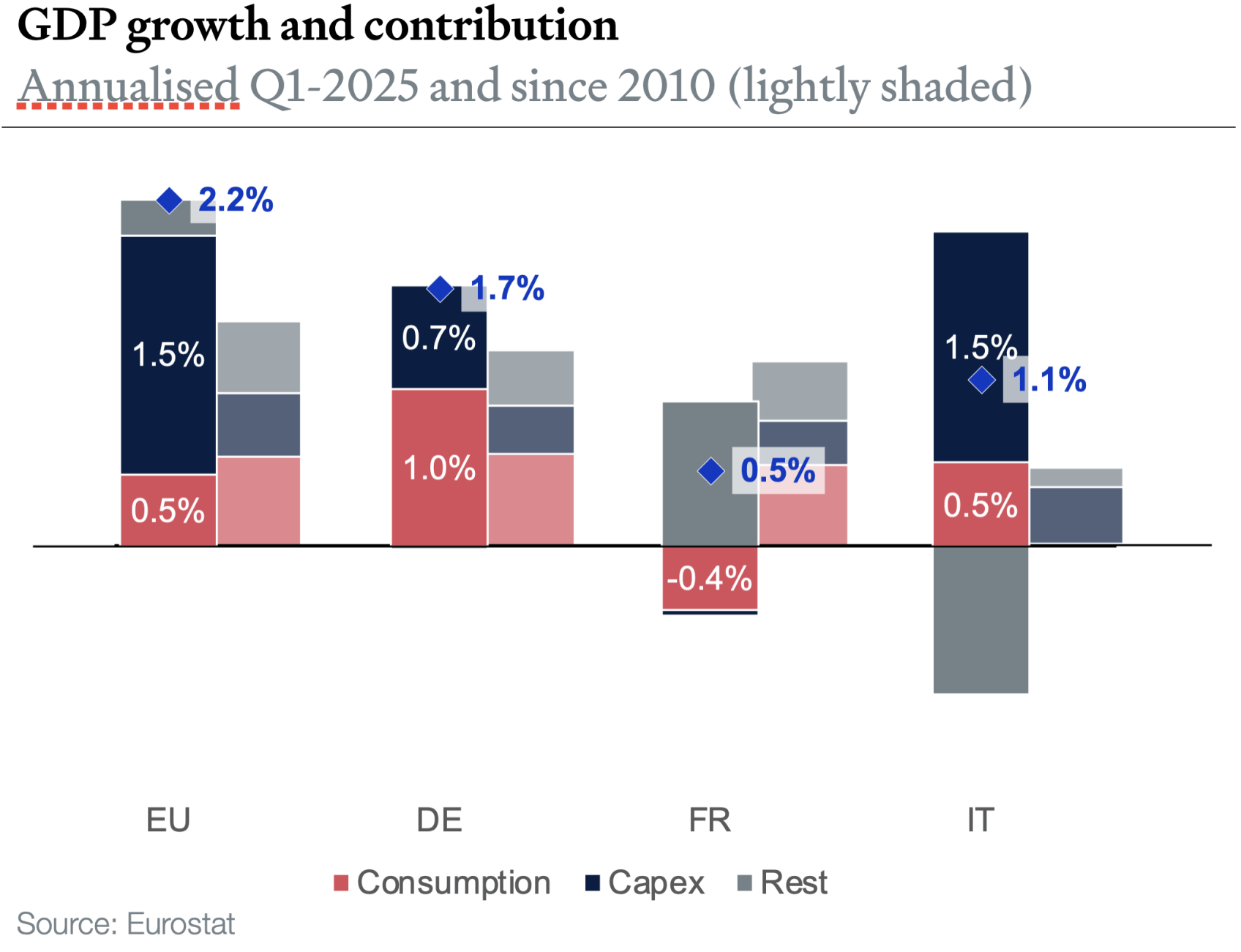

The weakness of consumer expenditure has been a recurring theme in coverage of the European economy, with growth of only 1% growth p.a. since 2010 across the EU, as well as in Germany and France. Italy stood out with zero real consumer expenditure growth over the past 15 years. This has continued in the beginning of 2025: Capex has contributed 4-times as much as consumption to growth. On a positive note, consumers in Italy and Germany increased spending above historic trend.

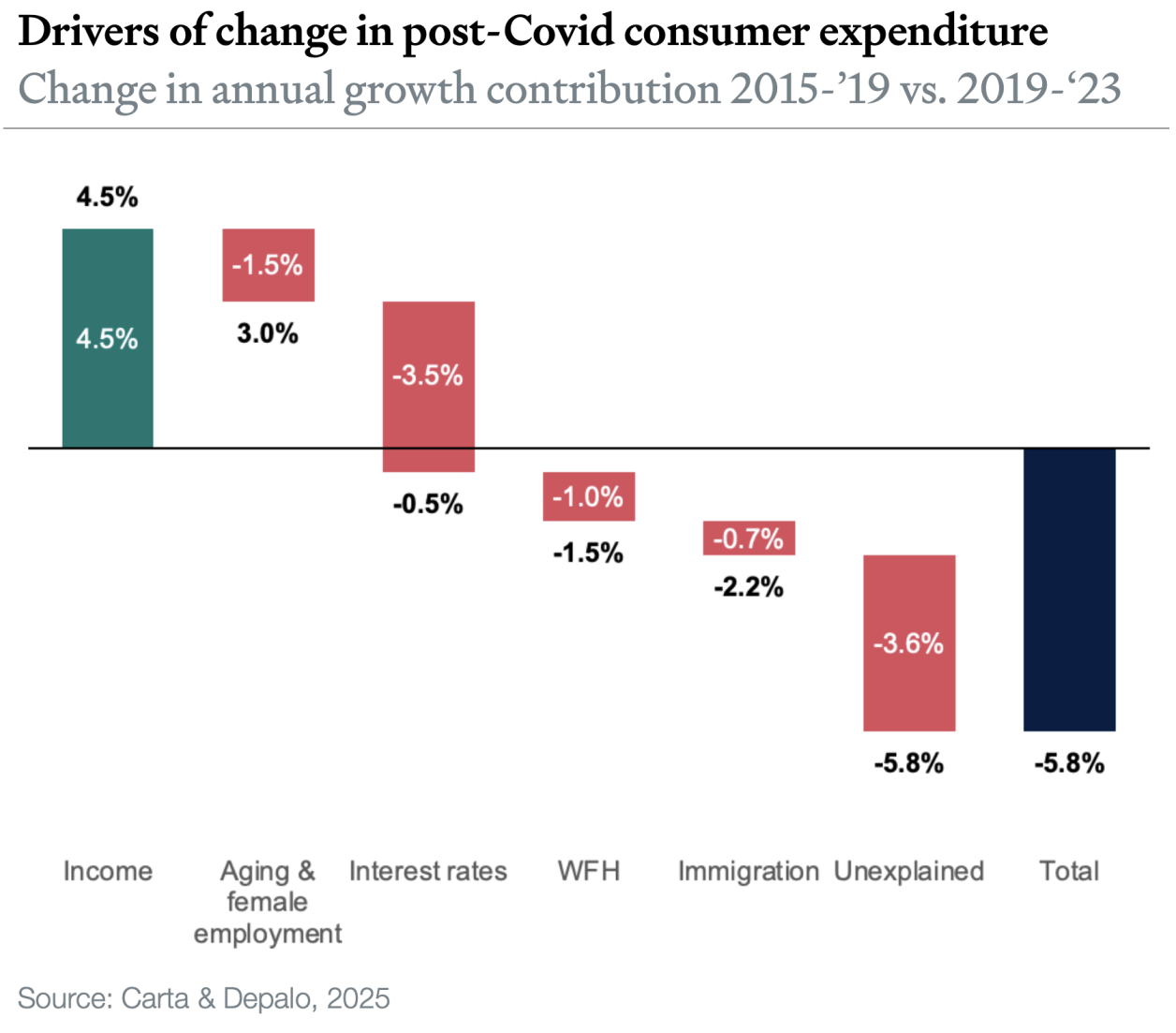

There is a wealth of research on the drivers of weak consumer spending, with most approaches taking either a highly macro, global trade perspective (cf. Trade Wars are Class Wars) or focusing on behavioral explanations. The (seemingly infinite) chain of crises since 2019 provide a fascinating real-life laboratory for consumer behavior. Two recent research notes by the central banks of Italy and France respectively analyzed the data to provide some interesting insights into the European consumer.