While a few large corporations often dominate headlines, research reveals a broader trend: industries across the economy have become more concentrated, with not only the biggest firms but also mid-sized ones expanding their market share. This shift is not a recent phenomenon: Since the 1930s, the share of the U.S. economy controlled by the top 1% of companies (ranked by assets) has risen from 70% to 90%. Even more strikingly, the top 0.1% share has doubled, increasing from 47% to 88%.

The pace of concentration has varied by industry. Before the 1970s, manufacturing and mining saw the most growth in corporate dominance due to mass production and economies of scale, which helped reduce fixed costs. After the 1970s, industries like retail, wholesale, and services experienced greater concentration, fuelled by advances in information technology. Across multiple measures, the dominance of large firms has increased steadily over the past century. In addition to asset concentration, revenue share among the largest companies has grown significantly. The top 1% of firms by sales now account for 80% of total revenues, up from 60% in 1970. Although the share of net income has fluctuated, the long-term trend is clear: by 1975, the top 1% of firms by net income were earning $8 of every $10 made by U.S. corporations, compared to $6 of every $10 five decades earlier (Jacobs, 2022).

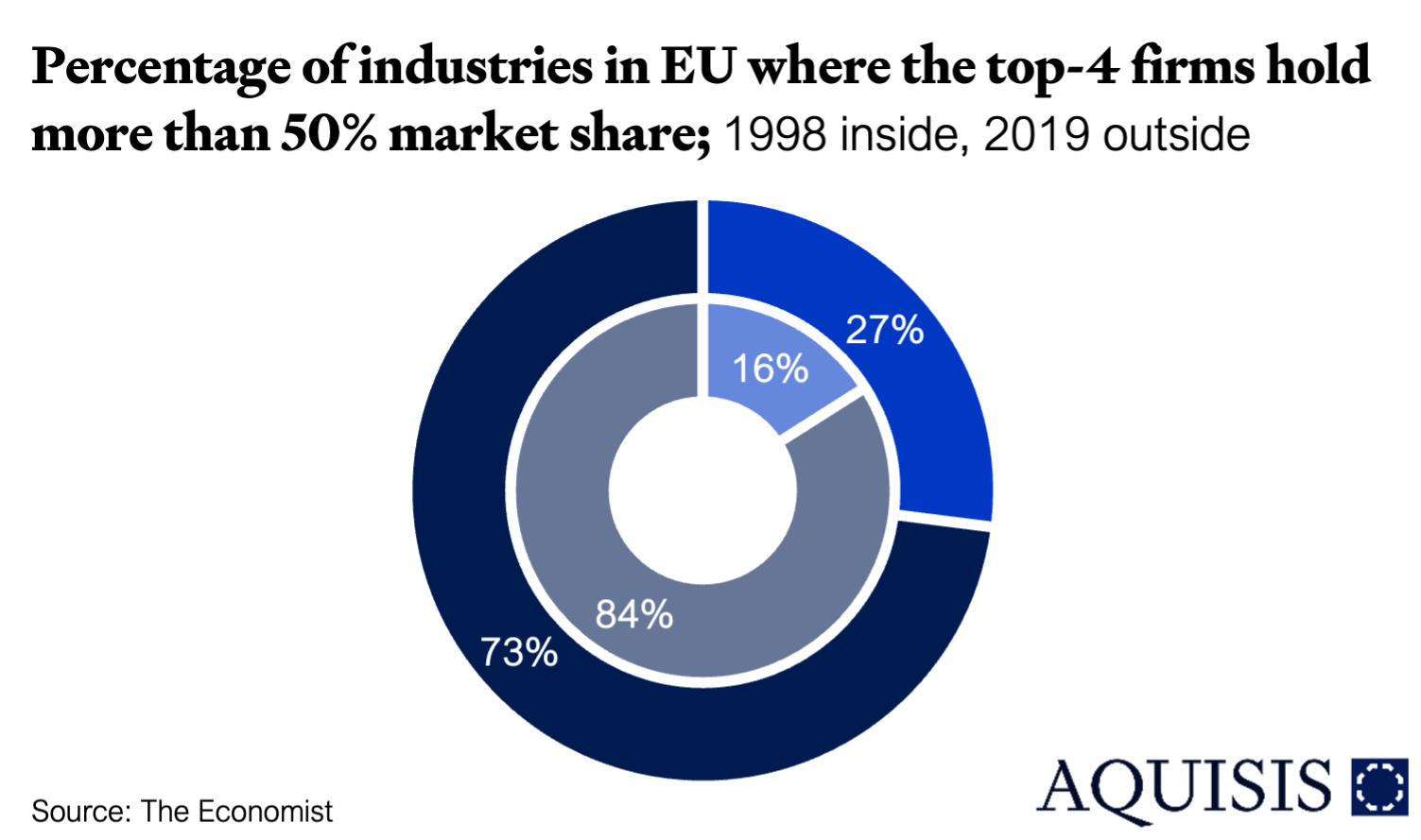

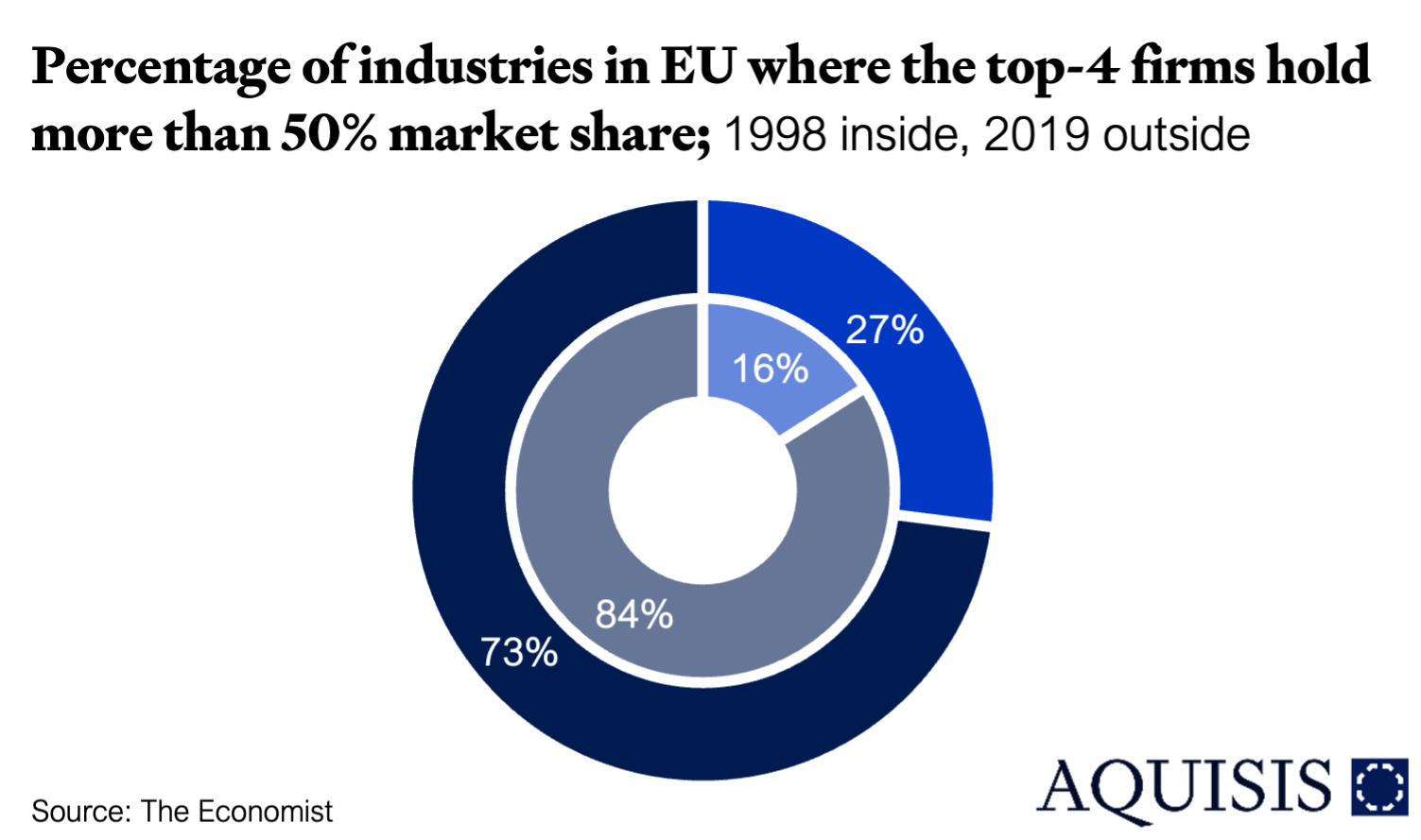

This trend is not limited to the United States. Between 1998 and 2019, the market share of the four largest firms increased in 73% of approximately 700 industries across Europe, with an average growth of seven percentage points. The proportion of industries where the top four firms controlled more than half of the market rose from 16% to 27%, with the most significant increases observed in Britain and France. Simultaneously, incumbent firms have become more entrenched. In Britain, the average number of firms that remained in the top ten of their industries by market share after three years was five before the financial crisis; this figure has since risen to nearly eight (Wars, 2023).

The persistent rise in corporate concentration reflects increasingly powerful economies of scale. As industries evolve, their level of concentration correlates with technological advancements. More broadly, the timing of rising concentration aligns with increased investment in research and development (R&D) and IT. These factors are directly tied to technological changes that enhance economies of scale. Moreover, as industries grow more dependent on R&D and IT, they may require larger-scale production to capitalize on shifting consumer preferences.

The effects of increased market concentration are debated, with some viewing it as a sign of rising market power, while others see it as a natural outcome of intensified competition.

The market power perspective suggests that a company with market power can influence the prices of its products and services, as well as the rates it pays suppliers and employees. Firms can leverage this power to generate excess profits by raising consumer prices, engaging in price discrimination, suppressing wages, deterring new competitors, or using their influence to shape regulations and government incentives in their favour (Haworth, 2019).

The alternative perspective suggests that concentration is a byproduct of intensified competition. In this "winner-take-all" scenario, heightened price competition forces less efficient firms out of the market. Greater price transparency, possibly facilitated by the internet, has shifted the competitive landscape in favour of highly efficient firms, enabling them to capture a larger share of sales. Unlike firms with entrenched market power, these market "winners" must continuously innovate, invest, and maintain competitive prices to avoid being overtaken by more efficient rivals. Consequently, this form of competition appears more beneficial, fostering innovation, productivity, and overall economic efficiency. In Europe, labour productivity increases by approximately 15–18% when moving from one decile to the next in the firm size distribution. This suggests that rising concentration is, at least in part, the result of a reallocation of revenue shares from less productive to more productive firms (E. Viegas, 2021).

While these two interpretations have distinct macroeconomic and market implications, distinguishing between them is challenging, as both contain elements of truth. This complexity is evident in two key consumer issues: Data Privacy: Concerns about data privacy, particularly in the technology sector, underscore the pervasive influence of major corporations. These companies provide innovative products and services that benefit consumers, yet their expanding dominance raises concerns about market power beyond just big tech. Price Transparency: The trend toward greater price transparency and intensified price competition, characteristic of the "winner-take-all" dynamic, is evident in sectors like retail. Online shopping has made price competition more visible, challenging traditional assumptions about how firms exert market power.

These two narratives are not necessarily mutually exclusive. Market power is not inherent; it must be acquired. Competitive disruptions may initially reward the most productive firms, placing them in dominant positions. However, once established, these firms may seek to protect and exploit their market advantage in ways that ultimately hinder broader economic welfare. Different industries may be at varying stages of this transition, meaning that both phenomena, heightened competition and increasing market power, can coexist simultaneous.

Costs of market concentration: Rising prices and declining competition

Yet, on balance a growing body of research suggests that increasing market concentration is reducing competition, suppressing wages, hindering startup growth, widening inequality, and weakening local economies. The evidence is clear: industry consolidation leads to higher prices (Tepper, 2018). A 2016 study by Bruce Blonigen and Justin Pierce of the U.S. Federal Reserve found that mergers drive price mark-ups with little indication of improved efficiency. Similarly, economist Matthew Weinberg’s 2007 analysis of two decades of mergers revealed that most resulted in price increases.

Further supporting these findings, John Kwoka, a professor at Northeastern University, analysed nearly 50 studies covering over 3,000 mergers. His conclusion was striking: when a merger reduced the number of significant competitors to six or fewer, prices rose in almost 95% of cases. Today, nearly 90% of announced mergers are successfully completed, with most withdrawals occurring due to companies backing out rather than regulatory intervention. According to the Antitrust Institute, which advocates for stronger competition enforcement, merger oversight in moderately concentrated industries has virtually ceased.

As businesses expand, significant consolidation is also anticipated in private fund markets. David Layton, CEO of Partners Group, envisions a dramatic reduction in the number of fund managers, shrinking from over 11k today to approximately 100 major players within the next decade. Recent high-profile acquisitions reflect this trend. BlackRock finalized a substantial $12.5bn cash-and-share deal with Global Infrastructure Partners last month. Adding to this wave of consolidation, Wendel Group marked the beginning of 2024 with its acquisition of IK Partners.

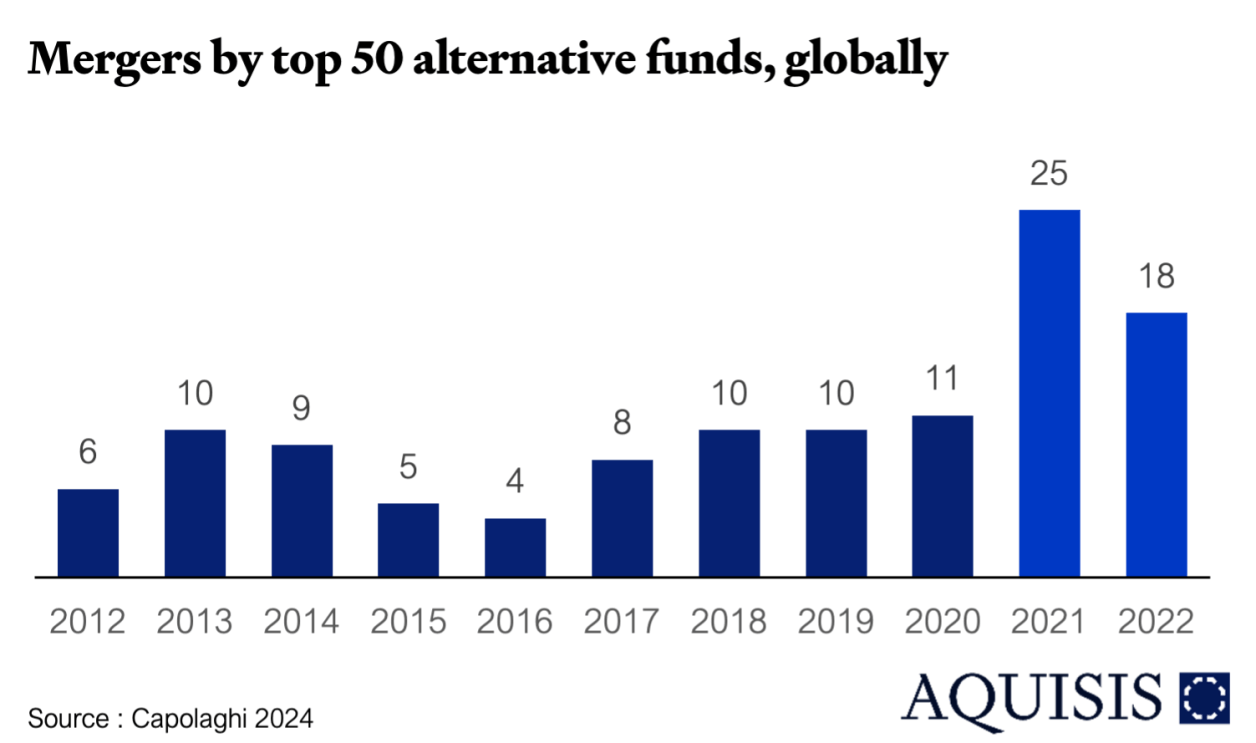

Looking at past trends, strategic acquisitions among the world’s 50 largest alternative asset managers more than doubled from 11 in 2020 to 25 in 2021. In 2022, there were 18 such transactions, making it the second-highest total of the past decade. This momentum is expected to continue into 2024 (Capolaghi, 2024).

A key driver of consolidation in private equity is the pursuit of diversified investment strategies. Large asset managers are increasingly expanding their capabilities to offer a broader range of investment options. Many are shifting from specialized or niche firms to multistrategy asset managers, positioning themselves as comprehensive service providers for limited partners (LPs). Investor preferences also favour larger firms. In Europe, private equity funds exceeding $1bn account for nearly 82% of all capital raised, highlighting a strong inclination toward well-established players. At the same time, rising regulatory scrutiny has increased compliance costs, creating significant challenges for smaller firms that struggle to keep up.

Succession planning is another major factor driving consolidation. As founders of boutique firms near retirement, many seek succession strategies, making their firms attractive acquisition targets for larger private equity players.

This ongoing transformation highlights the increasing concentration and strategic diversification within private equity and the broader business landscape. While some view consolidation as a driver of efficiency and competition, evidence suggests it often diminishes market competition, raises prices, and restricts economic mobility. As regulatory oversight lags, ensuring a balance between market efficiency and fair competition will be essential to preventing entry barriers and sustaining competitive dynamics.

Associate

Managing Partner

Capolaghi, L. (2024). Big gets bigger: How consolidation is reshaping Private Equity? Ernesty and Young.

E. Viegas, 1. S. (2021). Why free markets die: An evolutionary perspective. 1Complexity & Networks Group and Department of Mathematics,. London.

Haworth, R. (2019). Increased corporate concentration and the influence of market power . Barclays.

Jacobs, R. (2022, August 15). Rising Corporate Concentration Continues a 100-Year Trend. CBR - Economics.

Michele Fioretti, J. H. (2024). Prices and Concentration: A U-shape? Theory and Evidence from Renewables∗.

Tepper, J. (2018). We are all losing out as corporate concentration grows. Financial Times.

Wars, S. (2023, July 12). Is big business really getting too big? The Economist.

Drag & Drop Website Builder