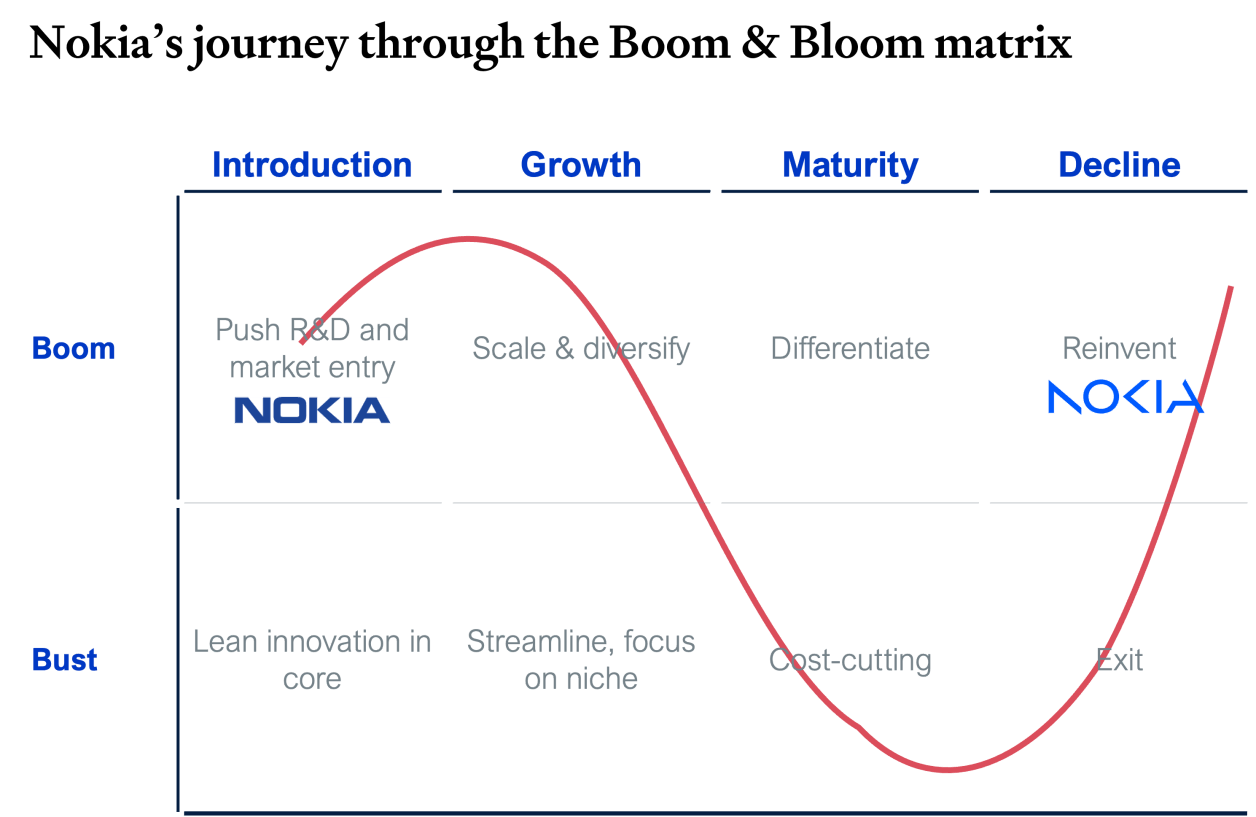

Case study: Nokia's journey

A notable example of strategic adaptation is Nokia. Few companies have played the full spectrum in the recent path like Nokia: In the Introduction Phase (early 1990s), the mobile telecommunications industry was in its infancy, marked by high R&D costs and limited competition. During this period of global economic growth, Nokia transitioned from a diversified conglomerate to a telecommunications company, heavily investing in mobile technology R&D. As the industry entered the Growth Phase (mid-1990s - early 2000s), mobile phone adoption surged, competition intensified, and technological advancements such as GSM networks emerged. With strong economic expansion fueling consumer purchasing power, Nokia capitalized on the demand by introducing mass-market, user-friendly devices like the Nokia 3310, scaling production, and expanding globally to become the market leader.

However, in the Maturity Phase (mid-2000s - early 2010s), mobile penetration reached saturation, and competition from Apple and Samsung disrupted the market with smartphones. The 2008 financial crisis further constrained consumer spending, shifting demand towards affordable smartphones. Nokia struggled to transition to the smartphone era due to its late adoption of touchscreens and app ecosystems, leading to a significant loss in market share. The Decline Phase (2010s) saw the mobile phone industry overtaken by smartphone ecosystems. As economic recovery spurred new consumer preferences favouring app-driven smartphones, Nokia attempted a comeback with Microsoft’s Windows Phone OS (Lumia series), but it failed to gain traction.

In 2014, Nokia sold its mobile division to Microsoft and shifted its focus to network infrastructure. In the Rebirth & Transformation Phase (2015 - Present), the telecom industry evolved with the rise of 5G, IoT, and cloud networking. As global investment in digital infrastructure surged, Nokia repositioned itself as a leader in network solutions, acquiring Alcatel-Lucent and investing in 5G, cloud services, and industrial automation. Today, Nokia competes with Ericsson and Huawei in the 5G market, demonstrating its ability to adapt and reinvent itself in response to industry and economic shifts.